Hints on Crashing/Ditching

Disclaimer

The information contained on this page is for general information purposes only. The information is provided by Rod Lovell and while he endeavours to keep the information up to date and correct, he makes no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the page or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the page for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk. In no event will he be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this Page.

Your Aircraft Flight Manual, Operations Manual or Pilot’s Handbook, may have information on this emergency procedure.

- “When the engine stops, the insurance company owns the airplane”.

- So use the plane to your advantage to absorb the impact forces.

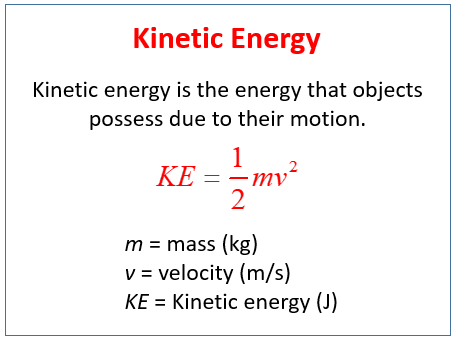

- Thus, the most important issue in Crashing/Ditching is to minimize the kinetic energy.

- The destruction of the aircraft is accepted, to provide the crew and passengers safe escape.

- YOU decide on your speed, but physics decides whether you live or die.

- The skill and performance of the flight crew is a key factor in any Crashing/Ditching maneuver

- Do NOT stretch the glide – it does not work.

- Make sure your seatbelt AND SHOULDER STRAPS are tight.

Crashing

Know your actual aircraft stall speed (not the stall warning speed) for each configuration and weight.

If you impact an object at (say) 120 kts, you will have FOUR TIMES the impact force than if you impacted at 60 kts.

- If the pilot is able to have some control over their aircraft then attempting to land in a clear area with a slow forward speed and slow rate of descent is the best way to ensure the aircraft remains intact.

- The idea is to get the aircraft onto the ground with as little impact energy as possible.

- One of Bob Hoover’s favourite pieces of advice for new pilots was this:

When faced with a forced landing, fly the airplane as far through the crash as possible. - If your only option is to put it in the trees, try to avoid the big trunk trees. If all the trees have big trunks, try to place the aircraft between the big trunked trees.

Another suggestion, pull back hard on the stick just before impact so the floor helps protect you, or stall the plane just above the trees. - If you are above a canopy of trees, you may consider actually stalling the aircraft just above that canopy so the stalled wings descend onto the canopy thereby absorbing a lot of the downward impact force.

- It’s all about flying your aircraft all the way to a stop. Unless you have the misfortune of hitting a big tree straight on, your survival depends on maintaining positive control of your aircraft.

- When approaching the trees, land into the wind and slow down to a controllable speed just above the stall for the softest impact.

- Fatalities usually result from loss of control.

- Remember, when the fan stops, you don’t own the plane any longer.

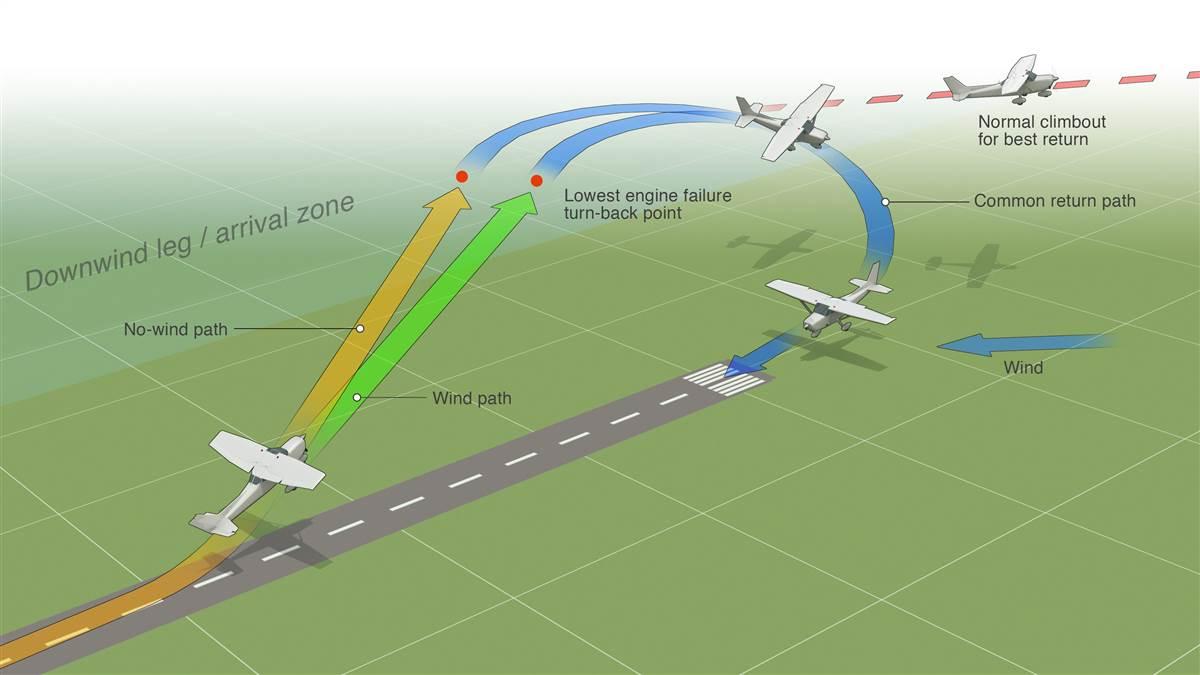

The Impossible Turn – or is it?

Here is something to consider from AOPA : Technique: A better return policy. Maximize your advantages on departure

Engine Failure After Takeoff

© Barry Schiff

Ditching

Is ditching Taboo?

– nobody wants to talk about it!

How many times does a plane have to tell the pilot it does not want to fly?

To even consider that ditching is the best decision for the SAFETY of the pasengers, is totally foreign to a General Aviation pilot (or airline pilot, for that matter) and the commitment to believe that you have sufficient skill and expertise would most likely scare off any further thoughts of going down that path!

- I can think of a few fatal accidents where if I had been the Captain, I would have seriously considered ditching the aircraft as an option.

- Having been trained in both the military and airline system, where Operations Manuals are the Bible, I am saddened, but understand, when some crews dare not think outside the square if an unusual situation arises.

- Ditching performance analysis of aircraft ditching can be subdivided into four major consecutive phases: approach, impact, landing and floatation phase.

- The pilot only has control over the approach phase.

- The approach phase covers the approach conditions for the airborne aircraft close to the water surface, which are then the initial conditions for the impact scenario.

- The approach conditions consist of the aircraft’s state of motion such as flight path angle, pitch attitude and aircraft speed. Moreover, the aircraft’s mass properties regarding weight, center of gravity and inertia as well as the flap setting, landing gear position, and engine thrust are of relevance.

- The environmental conditions contain wind and sea state. The decisive aspect about of the approach phase is to reduce the energy which has to be absorbed and transformed during the impact phase to a minimum.

- The reduction of the kinetic energy at the end of the approach phase can be achieved by reducing the aircraft weight by possible fuel jettisoning and, if possible, by using a maximum-flap configuration to lower the speed.

- Above all, the forward speed should be minimized while keeping a low to moderate sink rate, as the velocity directly determines the hydrodynamic pressure.

- What is important is the approach. Ditch parallel to and near the crest of the swell unless there is a strong crosswind. If there is a strong crosswind, ditch into the wind, making contact on the upslope of the swell near the top. Wave motion is indicative of wind direction, but swell does not necessarily move with the wind. Conditions of water surface are indicative of wind speed.

- Approach Technique

- In order to attain optimum impact conditions, adjust power during the final stages of the approach to maintain a steady rate of descent of 100 FPM at ditch speed, preferably for the last THREE minutes. Establish the final approach configuration early. The most favourable touchdown altitude will result from flying the configuration, rate of descent, and airspeeds recommended in this section. If the aircraft bounces on initial contact, keep the nose up.

- The ditching speed is so important. Try to ditch at Vs +10 kts or 1.1Vs, whichever is the higher.

- Kinetic Energy is calculated as half of the object’s mass multiplied by the velocity squared.

Once the plane has contacted the water the Pilot has very little control over it.

As a pilot who has thousands of hours flying P-3 Orion aircraft over great expanses of water, we used to practice ditching (using a simulated sea level of say 2,000ft or 5,000ft etc). And also as one who is a member of the Goldfish Club (having carried out a successful ditching), I believe I have the right to comment.

That is why it is so important to impact terra firma or the water at the lowest safe velocity.

If power is not available, establish best glide speed (best lift over drag speed) and accept the resulting rate of descent. In both cases, just above the water, flare to the manufacturer’s recommended touchdown attitude and hold that attitude to (and during) the touchdown, preferably at Vs+10kts. Remember that the flare height will be slightly lower than for a normal landing because the gear is retracted. It is imperative that the aircraft be flown onto the water and NOT stalled.

Think about it –

Talk to your fellow aviators – NOW

But for Pete’s sake don’t just sit there and crash –

do something.